The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire

BY STEPHEN KINZER

ST. MARTIN’S GRIFFIN, 336 PAGES, $9.89

–

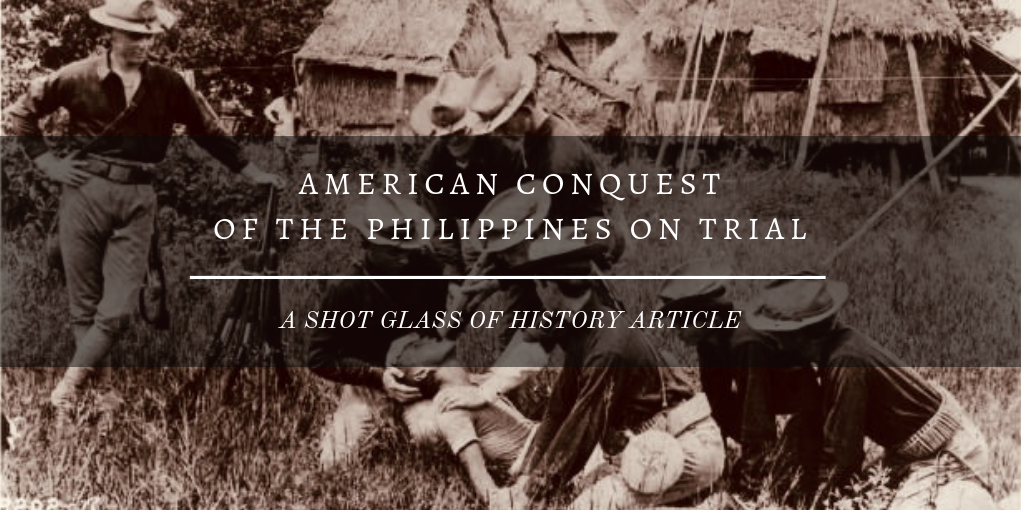

By the end of the 19th century, America’s borders had spread across the continent from shore to shore. However the American victory in 1898 against the Spanish forced the nation to decide whether it would join the empires of Europe and take possession of overseas colonies. Republicans under the presidency of William McKinley jumped at the opportunity, while a passionate, anti-imperialist movement floundered as the U.S. army triumphantly took possession of the Philippines. Author Stephen Kinzer in his book, The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire, describes how the anti-imperialist movement was resurrected when reports started to filter back to the states of U.S. troops torturing and committing widespread atrocities against the Filipino civilian population. In response the anti-imperialists requested and managed to procure a senatorial investigation to look into the rumors.

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge

However, the pro-war leaders in Washington, alarmed at the growing public interest in the conduct of the war, quickly attempted to get the situation under control. Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts managed to obtain for himself the position of chairman over the Senate Committee, and for the next six months he busied himself with stacking the witness list with individuals guaranteed to present a favorable picture of the military’s execution of the war. Meanwhile, another pro-war senator, Albert Beveridge, took charge of the prosecution. Beveridge was more than willing to push the imperialist party line and “browbeat soldiers who testified about abuses and scorned critics of annexation as apologists for terror” (Kinzer, The True Flag, 217).

There was little doubt about which direction the hearing was being pushed towards. The appointed civilian governor of the Philippines, and future U.S. president, William H. Taft, testified while on the stand that “never had a war been conducted in which more compassion, more restraint, and more generosity had been exhibited than in connection with the American war in the Philippines” (p. 217). However Taft did admit that there had been “some retaliation on the part of small bands of Americans,” along with “some cases of unnecessary killing, some cases of whipping, and some cases of what was called the water cure” (p. 217). Despite such admissions, some of the more extreme members of the pro-war faction still refused to admit that any misconduct had been conducted by any troops. Secretary of War, Elihu Root concluded that “in substantially every case . . . the report has proved to be unfounded or grossly exaggerated” (p. 217).

The anti-imperialists were furious that despite the continuing reports of atrocities coming from the Philippines, the Republican senators in charge of the hearings refused to investigate further. The anger between the two parties resulted in heated shouting matches and even violent fist-fights breaking out on the senate floor.

However, things became more complicated when the hearing began to interview individual soldiers. Despite Lodge’s careful selection of eye-witnesses from the War Department’s “safe list,” the soldiers were embarrassingly open about the atrocities they had witnessed and committed. “No fewer than six said they had witnessed the ‘water cure,’ other tortures, or reprisal killings. All said, however, that these were reasonable tactics when fighting an enemy who showed what one called ‘inability to appreciate human kindness’” (p. 220). Even one of the commanders, General Robert Hughes, admitted that he had “routinely ordered the burning of Filipino villages in order to deny shelter to insurgents” (Ibid.).

As more and more such testimonies began to come out, the pro-war faction was forced to deny Senator Root’s stance that no misconduct had occurred, and instead followed Lodge’s suggestion, and admitted to some isolated instances of wrongdoing. The whole affair was becoming increasingly awkward. In two years President Theodore Roosevelt would be up for election for the presidency. He had been a staunch proponent of the war, and it would not do for him to look like he had implicitly tolerated war crimes. Instead he approved that several of the soldiers who had been implicated in war crimes be made scapegoats. However, the investigation quickly got out of hand when Major Anthony Waller revealed under questioning that General Smith had personally ordered him to engage in widespread extermination of the Filipino inhabitants and turn the land into a “howling wilderness.” Waller testified that Smith had said: “I wish you to kill and burn. The more you kill and burn, the better you will please me. I want all persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States” (p. 221). When Waller asked for a minimum age limit, Smith replied that it was to be ten years and older. “According to their own testimony, they razed every village they found, usually massacring civilians” (p. 222).

General Smith’s order appeared as a caption in the New York Journal on May 5, 1902. Above the U.S. shield the American eagle has been replaced by a vulture.

The story of “Howling Wilderness” Smith was flashed across newspapers all over the country. The New Orleans Times Picayune declared: “If we are to ‘benevolently assimilate’ Filipinos by such methods, we should frankly so state, and drop our canting hypocrisy about having to wage war on these people for their own betterment” (Ibid.). Roosevelt had little choice but to order that General Smith also be court-martialed.

Brigadier General Jacob “Hell-Roaring Jake” Smith, was a former Civil War veteran, who claimed to have learned his use of heavy-handed tactics while subjugating the American Indians. He was the perfect scapegoat for the war’s apologists.

In his first appearance before the Committee on the Philippines, he [Smith] denied that he ever gave orders to kill. Later testimony showed that this was a lie. Once caught, Smith reveled in the truth. He was quietly advised that the charges could be dropped if he testified that he had not expected his orders to be taken literally, but he defiantly refused to do so. Instead he proclaimed loudly that he had meant every word. That guaranteed his conviction. Secretary Root let him off with a reprimand on the grounds that he had been driven to excess by “cruel and barbarous savages.” Major Waller was acquitted. Many cheered. (Ibid.)

Despite the evidence brought to light in the Senate Hearing of troops committing widespread and continuing atrocities, nearly nothing was accomplished by it. Republicans rushed to defend Smith and the U.S. military. Harpers explained that the army, “[h]aving the devil to fight, it has sometimes used fire. Having liars to fight, it has sometimes used lies. Having semi-civilized men to fight, it has in some instances used semi-civilized methods. That was inevitable, and will be inevitable as long as soldiers are men” (Ibid.). One general, Frederick Funston, even went so far as to declare: “I personally strung up thirty-five Filipinos without trial, so what was all the fuss over Waller’s dispatching a few treacherous savages?” (p. 223). Funston then declared that anti-imperialists who protested the war “should be dragged out of their homes and lynched” (Ibid.). Upon reading this report, Mark Twain volunteered to be the first lynched, and wrote that Funston’s “conscience leaked out through one of his pores when he was little” (Ibid.).

Meanwhile, the war was being brought to its brutal conclusion. In a final push to defeat the Filipinos, General Franklin Bell ordered that all natives in the region of the conflict be forced from their homes and sent to fortified “reconcentration” camps. Outside of the camps the troops employed a scorched earth policy. All Filipinos “not actively aiding the U.S. force must be killed; crops must be burned and livestock destroyed; and a native would be selected by lot for execution every time an American was killed” (p. 224). Cut off from any source of supplies, the insurgents were forced to surrender. “Fifty-four thousand civilians died during Bell’s three-month campaign” (Ibid.).

Several months later, on July 4, 1902, President Roosevelt’s declared that the Philippine War was officially over, and he thanked the American soldiers for their “self-control, patience, and magnanimity” (p. 225). In a period of over forty-one months, the 120,000 American soldiers committed to the Philippine War had killed more Filipinos than the Spanish had during their three hundred and fifty year long occupation. In the end approximately 20,000 Filipino soldiers were killed, and hundreds of thousands civilians died, either directly or as a result of the American conquest. The United States would continue to rule the Philippines until finally granting them independence nearly forty years later, on July 4, 1946.

Despite President’s Roosevelt’s declaration that the war had ended in 1902, fighting continued for years afterwards. In this photo taken in 1906, U.S. soldiers pose after the Moro Crater Massacre, in which 994 men, women, and children were killed. Only six members of the Bud Dajo village survived.